How 40,000 years after the first Australians arrived, Australia was “discovered” again

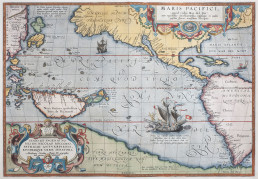

From Ptolemy in the 2nd century AD, geographers postulated that a great southern continent had to exist, to counterbalance the weight of the known northern hemisphere and prevent the world from tipping over. Through the ages, contemporary maps showed various representations of the unknown great southern land, using a multiplicity of geographic names.

Abraham Ortellius (1527-1598) Theatrum Orbis Terrarum (1570). Silentworld Collection SF000822.

In Marco Polo’s account of his 1292 travels to India and China he referred to Locach as a kingdom where gold was “so plentiful that none who did not see it could believe it”. Sixteenth-century maps from a range of cartographers show Beach appearing on maps of the time as the northernmost part of the southern continent, along with Locach. Beach is believed to be a mistranscription of Locach, as in German cursive script “Locach” and “Beach” look similar. Historians today largely believe that confusion as to the location of Java Major (the ancient kingdoms of Champa being present-day Vietnam and Cambodia) and Java Minor (being Sumatra), resulted in Beach erroneously being located more than a thousand miles south of Sumatra. Consequently, some geographers believed that Beach/Locach was near, or was an extension of, the unknown Terra Australis and this error was repeated across most maps of the time

On a separate note, this confusion, together with a range of maps such as the fabled Dieppe maps of the 1500s rumoured to be based on stolen Portuguese originals, showing outlines of Beach or the southern land with Portuguese place names have led to ongoing speculation as to whether the Portuguese reached Australia sometime around 1520, some 86 years before the first recorded European visit to Australia by the Dutch navigator Willem Janzoon in the Duyfken in 1606. There is no firm evidence to support this claim, but in places, a number of tantalizing similarities exist between some of these early maps and the actual Australian coastline.

As an example, the image of Terra Australia Incognita engraved by Theodore de Bry in 1599 above shows considerable similarity with the actual geography of Cape York on the right, yet the first European visit to Australia by Willem Janzoon in the Duyfken would not take place for another seven years.

The Portuguese were extraordinary seafarers and navigators. For a little country of only around a million people, Portuguese caracks and caravels set sail into unknown seas from the 1300s onwards with their golden age of exploration being the 15th and early 16th centuries. Extraordinary visionaries such as Prince Henry the Navigator sitting in his cliff top castle in Sagres in the Algarve sent wave after wave of brave sailors down the west coast of Africa in an attempt to find a maritime route to Asia to break the Venetian and Arab stranglehold on the import of silks, spices and other precious commodities overland from the Middle East.

Bartholomeu Diaz finally rounded the Cape of Good Hope in 1488, followed by Vasco da Gama who reached India in 1498 and started an immense flow of maritime trade between Asia and Europe.

At its peak, in the early 1500s, the Portuguese empire extended from Brazil to all of Africa, the Middle East, India and most of Asia. The Portuguese near monopoly on the maritime spice trade with Asia lasted the best part of 100 years before eventually being displaced by the Dutch, English and others.

Three Master Carrack. Breugel the Elder, 1565. Silentworld Collection SF001134.

As can be seen from the map below, however, tantalisingly the one country that does not appear in any historical accounts as having been reached by the Portuguese is Australia.

Portuguese maritime exploration from 1400 to 1550.

However, the Portuguese had reached Timor around 1512 and at only 680km away, the Australian coast would have been less than another week’s sailing. Did the Portuguese come all the way from Portugal to Timor and for nearly 100 years never sail the extra week to Australia? There is no firm evidence to support that they ever did, but one would have to conclude that it is at least likely!

The Silentworld collection holds several other tantalising clues as well. Again, none of these constitute proof but they certainly stimulate the imagination! Below is an image from a Portuguese hymn book owned by a Portuguese nun Caterina de Carvalho, dated between 1580 and 1620.

Image from the Portuguese Processional, c1600. Silentworld Collection SF001060.

In the capital D can clearly be seen what looks like a kangaroo but as the hymn book was printed before the first recorded European visit to Australian shores, how did the author know about kangaroos? The sceptics say the image might not be of a kangaroo anyway, or note that there are tree kangaroos in New Guinea which the Portuguese also reached in the 1500s, so once again it is not proof that the Portuguese ever reached Australia, but it certainly provokes spirited debate amongst the believers and non-believers.

The Silentworld Foundation mounts annual maritime archaeological expeditions to far North Queensland and elsewhere, searching for early shipwrecks from centuries long past. Despite considerable success finding numerous shipwrecks from other nations, we have never found a Portuguese vessel of that era. However, we live in hope that one day amongst the coral we will find an artefact bearing a Portuguese armillary sphere or similar insignia, and if we do, the mystery will be solved and our history will need to be rewritten!

Michael Gooding

As a Captain for Silentworld Charters, Michael has experienced the wonders of Oceania first hand, and has cruised around this special region for nearly 30 years. His role as Captain includes being a part of the not-for-profit Silentworld Foundation. The Silentworld foundations annually undertakes an expedition that highlights the unique history of the South Pacific region and raises awareness for the stories that each expedition discovers. Combining his passion for the sea, exploration and maritime archaeology, Michael has helped create some special experiences for those on board Silentworld, showing how we can use yachts to truly engage with and protect the oceans we sail on.